On March 8, 2022, the nickel futures price doubled in hours on the London Mercantile Exchange as the market digested the information that a Chinese nickel manufacturer had defaulted on an enormous over-the-counter short position.

Caught off guard, London Metal Exchange executives cancelled about $12 billion worth of the day’s nickel contract trades. Afterwards, LME executives said they had no choice, because $19.7 billion of margin calls would have pushed a number of its clearing members to default, creating a systemic risk in the market.

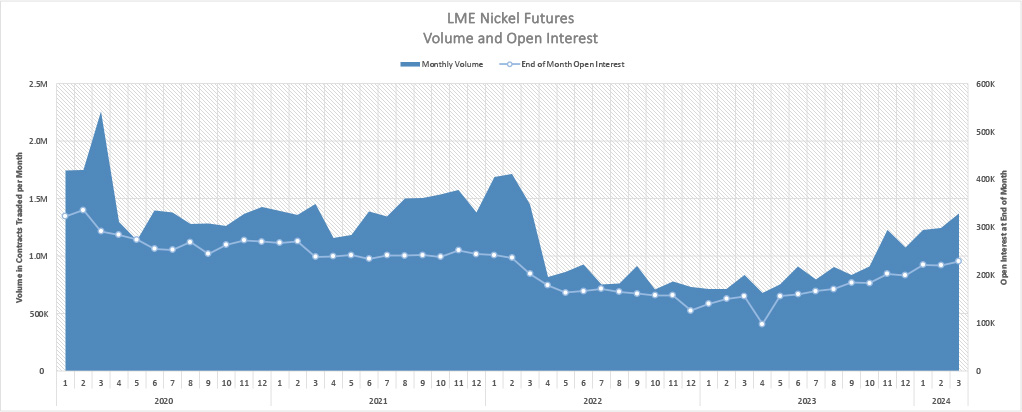

The decision shocked market participants and caused many firms to pull back from trading on the exchange. LME volumes fell abruptly after the cancelled trades, not only in the nickel contract but other metals too, and nickel volume lagged for months. Two major US market participants, hedge fund Elliott Associates and market maker Jane Street, went so far as to take the 147-year-old exchange to London’s High Court.

Although the court sided with the LME, affirming the exchange's right to cancel the trades, some market participants voted with their feet, closing out their positions and moving to other markets. This has been especially true of hedge funds that are not active in the underlying physical markets and do not need to use LME's contracts to hedge their market risk.

One example: Transtrend, a Dutch fund manager that trades futures across many exchanges. After the nickel crisis, Transtrend closed out all of its LME positions and exited the exchange. In a note published on its website, the company said that it had "lost confidence" in the LME because its decision to cancel trades was fundamentally at odds with the basic principle of well-functioning markets."

Building back better

LME executives have worked hard to win back investors’ confidence.

First, they commissioned Oliver Wyman, the consultancy, to conduct an independent review of the exchange and clearinghouse. On the consultants’ recommendation, the LME introduced a number of structural reforms that included a new volatility and price control framework, clear standards regarding eligibility of clearing members, and more standard pricing methodologies.

To address low inventory levels in nickel, the LME added four physical suppliers who could provide up to 100,000 metric tons of additional stock. These were primarily new Chinese refiners who are taking nickel ore from Indonesia, the source of most of the world’s new nickel supplies. “What that did is provide the contract with more depth around physically deliverable stock,” explained Robin Martin, LME's head of market development.

In 2023, the LME also began to require members to disclose their over-the-counter nickel positions on a weekly basis. Later, it extended this requirement to all its metals. Martin said this allows the exchange to get a more complete view of the market.

“We’re now in a position I think very unique amongst commodity derivative exchanges, where we get [information] from our members of their own OTC positions as well as those of all their individual clients, and then the LME is able to combine that with on-exchange information, and that gives our market surveillance colleagues a much better, quasi-real time view on what’s happening across both exchange and OTC markets,” Martin said.

Response to these changes seems to have been positive. “Our efforts to bolster liquidity and confidence in LME Nickel continue to deliver, with nickel ADV back to 2021 levels and up 76% on 2023 year-to-date,” said Martin.

Average daily volume reached 60,991lots were traded in the first quarter of this year, a 75% jump over the 34,840 traded in Q1 2023 – and the steepest growth of the LME’s six top metals.

Open interest has recovered only partially, however. At the end of February 2022, right before the crisis, open interest in LME's nickel futures stood at 236,000 contracts. That sank to just 126,000 contracts at the end of that year. Open interest began to recover in the second half of 2023, reaching 200,000 contracts at year-end and 223,000 at the end of March 2024.

Only game on earth

Although the reforms have gone a long way to restoring confidence in the exchange, another reason for the recovery is the lack of alternatives.

The only other major competitor for nickel is the Shanghai Futures Exchange, but its contracts are denominated in reminbi and access to that market is difficult for firms outside China. Although CME Group operates a well-established copper futures market in the US and has the resources to mount a challenge, it opted to focus on aluminium instead.

“A year ago, there was some doubt that the LME would endure as the main pricing reference,” said Jim Lennon, a veteran nickel analyst for Macquarie Bank in London.

Lennon argues that the main reason nickel traders came back is that they had no other place to go: the nickel market is too small to spread itself over multiple exchanges. Only three million tons of nickel were sold last year, he said – eight times less than copper, and 20 times less than aluminum.

“You can’t really split up the liquidity into different submarkets. I think most people have realized that the LME is not perfect but it is the best of what we have,” Lennon said. “You look around for alternatives and realize that there is no serious alternative.”

Robert Fig, a metals expert who now runs a commodity risk management consulting firm, also sees the limited scale as a barrier to entry. “There are not that many producers and consumers – there is no place in the world for a second contract, in my view,” said Fig, who worked at LME earlier in his career.

The LME’s Martin added that the exchange did not attract new competition these past two years because the physical delivery element of its contract is difficult to replicate. “I think that it’s testament to the fact that building a physically deliverable contract for the nickel market is actually quite complex,” he said.

Competition on the horizon

Nonetheless, two new competitors have emerged. Although neither one has launched trading yet, they both are looking to differentiate themselves from LME.

One is Abaxx, a startup exchange based in Singapore founded by a group of futures industry veterans. Abaxx plans to offer a futures contract based on nickel sulphate, a different grade of nickel that is used in electric vehicle batteries. The exchange has been gradually building the infrastructure to support its market, and recently signed up several clearing firms as members of its clearinghouse.

The other is Global Commodities Holdings Limited, a London company that plans to launch a trading platform for spot trading in physical nickel. The company is headed by Martin Abbott, who was the chief executive of LME for seven years and oversaw its sale to HKEX, and its shareholders include several large mining companies.

GCHL is working with Intercontinental Exchange with the goal of using the prices for nickel traded on its platform as the basis for a new futures contract. The two companies already have a history of working together – GCHL's platform is used for the trading of seaborne coal, and its coal indices are used for the coal futures listed on ICE Futures Europe.

“We are exploring the potential to do this and engaging with market participants and key stakeholders on how we can deliver an alternative market structure for nickel, using GCHL’s pricing, to deliver a better model for hedging which is more adaptable to a changing supply chain,” said Chris Rhodes, president of ICE Futures Europe, when the partnership was announced in March.

Looking ahead

Two years later, Fig still thinks the LME did the right thing. “This was an unusual situation that they had no control over. And they had to do something urgently to ensure that the market retained its integrity. From day one, I believed they should have done what they did.”

At the same time, however, Fig also noted that the risk that an outsized bad OTC trade will upset the market again has not gone away entirely. “That to me is the real issue: unless the LME is able to identify what’s going on in the whole market, they run the risk that this could happen again,” he said.

Another issue for nickel that the LME has tried to address is a call to launch a low-carbon nickel contract. LME executives have argued that volumes are such that the market could not support a second contract that might fragment liquidity from the LME’s established contract.

As an alternative, Martin said, the LME points to its partnership with the Metalshub spot-trading platform, which can offer buyers an alternative mechanism for low-carbon price discovery.

Metalshub has now begun to report monthly data on the transactions and market value of class 1 nickel traded, including the low carbon subset. LME officials say this could become the basis for a transparent, transaction-based premium.

The nickel market has also been beset by sagging prices. Earlier this year, some analysts worried that nickel supplies have grown enough in recent years that the price could fall below $15,000 a ton, at which point Fig said about 70% of all nickel producers would be operating below the cost of production.

Now, however, the war on Ukraine has come to the rescue. The UK and the US introduced sanctions on April 12 that seek to ban trading of aluminum, copper, and nickel produced in Russia from that date onwards, on the grounds that revenue from their sale is being used to fund the country’s invasion of Ukraine. The news has helped push the spot price of nickel up to $19,041 per ton.